News from the Archives

Despite the challenges of Covid-19, historical research is under way as part of the academic research project funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. ‘Gypsy and Traveller Experiences of Crime and Justice Since the 1960s’ brings together academics from the London School of Economics, the University of East Anglia and the University of Plymouth. This research aims to offer the first comprehensive study of Gypsy and Traveller interactions with criminal justice agencies alongside a study of the Gypsy and Traveller experience of victimisation and discrimination. Previously overlooked evidence from the National Archives, London Metropolitan Archives and a range of County Records offices are proving useful in informing this under-researched topic. Drawing on the skills of experienced researchers from the fields of sociology, criminology, and history, this interdisciplinary project is already producing fascinating results.

For centuries Gypsies and Travellers have suffered discrimination and have continually been stereotyped by the media, political classes and settled communities as having a parasitic relationship to wider society. The arrival of Gypsies and Travellers in a settled community are often greeted with fear and suspicion and their interactions with settled communities are also portrayed as being hostile. Indeed, the newspapers studied, paint a picture of Gypsies and Travellers as being violence-prone, disorderly and perpetrators of fraud. However, despite these persistent myths, there has been little in the way of extended academic research into this topic, exploring and quantifying the various forms of discrimination against Gypsies and Travellers in modern Britain.

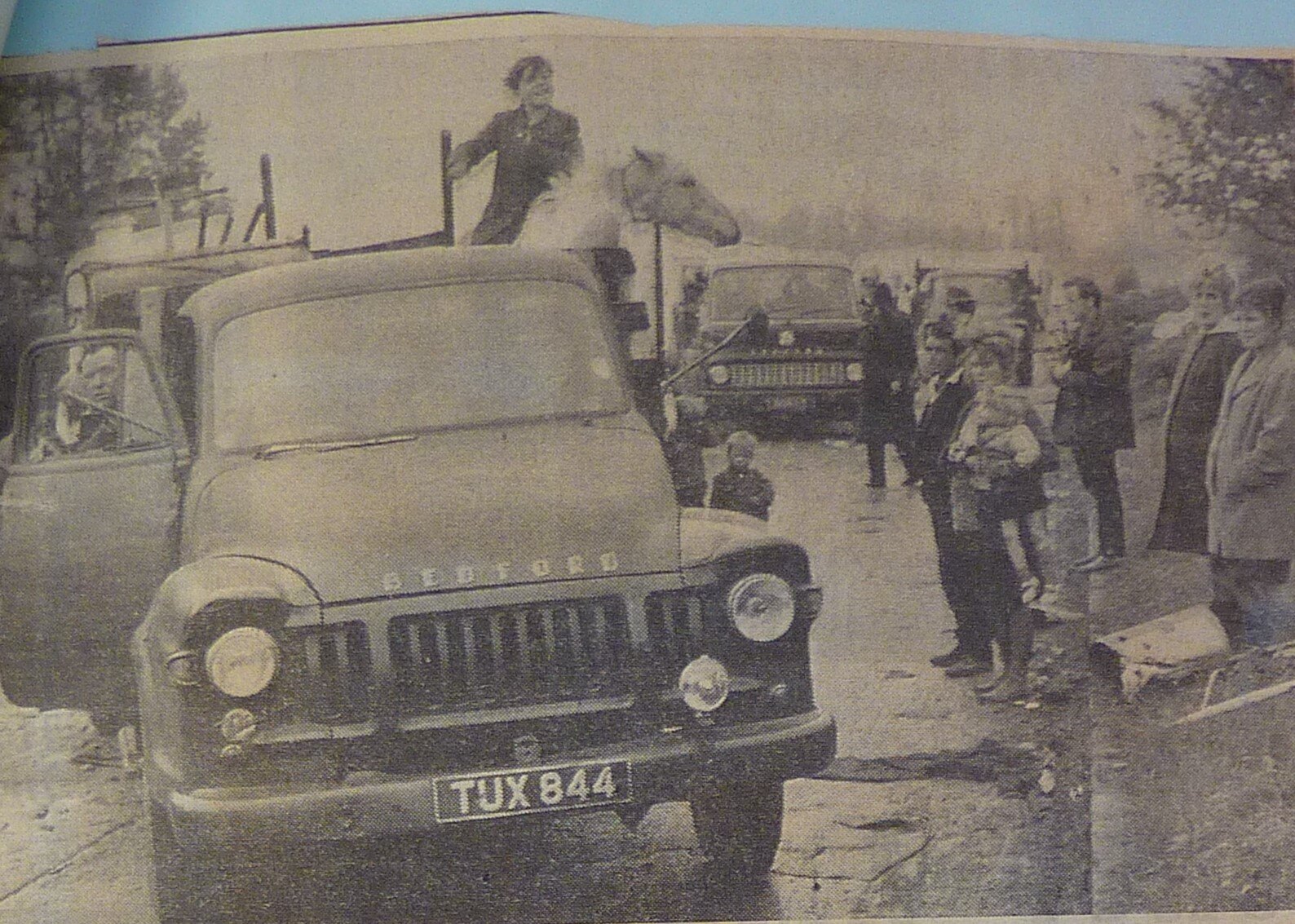

Image shows press clipping from The Gazette 15.5.1965 and depicts the eviction of Gypsies from the Patchway lay-by site by Thornbury Rural District Council.

Despite Gypsies and Travellers being protected under anti-discrimination legislation, archival research from this new project has thrown up plenty of examples of individual, collective and institutional prejudice. Among this, however, there is occasional evidence in local newspapers of positive coverage of Gypsies and Travellers. That said, this coverage is largely confined to those who fitted the romanticised caricature of the Gypsy or Traveller: complete with an ornately-decorated horse-drawn caravan, dwelling exclusively in the countryside and practicing centuries-old crafts. A Bristol Evening Post newspaper report, of 1967, describes so-called ‘genuine Gypsies’ who ‘wanted to live in the country, caused no trouble and wanted to stay there’ working as seasonal agricultural labourers. By the mid-1960s this was already a dated stereotype and Gypsies and Travellers who lived in modern motor-hauled caravans, seeking work in cities could expect a hostile reaction, being cast as mere ‘hawkers’ or unwanted itinerants. Indeed, a meeting of Cheltenham District Council in October 1966 saw Gypsies and Travellers cast as criminals and people who ‘pay no rates or tax’. This idea, that those dwelling in modern caravans and seeking work in urban areas were not ‘real’ Gypsies or Travellers, is one that appears repeatedly across the archives we’ve been finding. These stereotypes weren’t new in the 1960s. Even though after the Second World War, it became normal to have a motor vehicle and move to the city to work in factories or offices, somehow people thought that Gypsies and Travellers should be different. If they moved into modern trailers, started cooking on gas and running a vehicle, then suddenly they were no longer ‘real’ Gypsies.

Gypsies and Travellers also faced a set of unique challenges in the 1960s, the number of stopping places shrank and planning restrictions tightened, leaving many Gypsies and Travellers with literally nowhere to go other than unlicenced encampments. The Caravan Sites Act 1968 aimed to improve the situation, compelling local authorities to provide sites for Gypsies and Travellers. However, few councils took this duty seriously. For example, Avon Council, which includes the city of Bristol, had been ordered in 1968 to 80 pitches for Gypsies and Travellers. By 1991, they had provided only 12. The reasons for the failure to provide the proper number of pitches was admitted in a public meeting, held in October 1991. Avon County Council conceded that for the past 23 years had yielded to protests from local residents on the issue and had abandoned a number of plans for larger sites.

In the face of these challenges, it was perhaps inevitable that the police authorities would tun their attention to Gypsy and Traveller issues with renewed vigour. One of the most significant discoveries so far has been files of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) held by the University of Hull. A speech by the Chief Constable of Kent, at the 1962 ACPO Conference, demonstrates that senior Police officers were prepared to uncritically spread myths about the ‘true’ Gypsies and Travellers of the pre-war period, telling his fellow officers, ‘before the last war there were more “true gypsies” who lived in the main by their own rules…though their standards of life was quite different from that of the general public they were quite well disciplined and although they lived on the land they seldom seemed to commit any serious crime. Their major offences being poaching and pilfering’. The Chief Constable drew a comparison with modern day Gypsies and Travellers, ‘the main difference being the transition from the horse-drawn to the motoring era. The Gypsies have been joined by many low-class dealers and layabouts who are not prepared to work regularly nor to accept the normal responsibilities of citizenship. Their offences now being related to metal thieving and motoring… they are not true nomads and having found a camping site will use every artifice to remain undisturbed’. In the eyes of the Chief Constable of Kent, the problem was not so much that they committed crime, but that their alleged offences had moved with the times. He also bemoaned the fact that complaints against Gypsy and Travellers cannot ‘be dealt with so easily as they were before the war because of the cunning knowledge of the law that these people have attained, particularly so since their cause has been backed by certain well-meaning and influential persons’.

Similarly, a letter from the Chief Constable of Bedfordshire police written to the General Secretary of ACPO in April 1982 commented that ‘I can see no need at all for the general well-being of this country nor its solvency in these times of economic stringency to have facilities for gypsies and tinkers to be able to hove too at suitable locations as they move about selling their second-rate made up lengths of carpet and indulging in dealing in scrap metal… it could only be achieved at a cost to the people who follow a more traditional way of life and make a far greater contribution to the economics of this country and regularly pay taxes’. These two pieces are the most blatant examples of anti-Gypsy and anti-Traveller prejudice in the ACPO files but a number of other documents seem to see the role of the Police to protect settled communities from the ‘threat’ posed by Gypsies and Travellers and bemoan their lack of powers to achieve this. Senior police officers of this era do not even give lip-service to the notion of treating Gypsies and Travellers equitably or consider that they themselves may be victims of crime and harassment, seeing them almost exclusively as a ‘problem’.

The ACPO files have turned up plenty of valuable material but the voices of Gypsies and Travellers themselves are almost wholly absent from the record. As the historian David Mayall has claimed, sources on Gypsies and Travellers have been subject to ‘gaps, errors, repetition and romanticising’ and have largely been produced by outsiders (Mayall, 2004, p. 39). This is something that has certainly been reflected in the archival research to date. As the project develops, these official accounts will be balanced by oral history testimonies from members of the Gypsy and Traveller communities, offering future researchers a more comprehensive view.

Sources

Gloucester County Archive. File D94/3/29

Gloucester County Archive. File K552/13

David Mayall, Gypsy Identities 1500 -2000: from Egipcyans and Moon-men to the Ethnic Romany. (London: 2004).

Open University ACPO Archive, Milton Keynes. File GP/28